Stimulate future progression

As a systems supplier to the glass industry, Eurotherm by Schneider Electric is deeply involved in these types of discussion, with an interest in future progression. The company may be considered partially biased, because electrical heating systems are part of its business. Nonetheless, it recognises the importance of participating in these conversations with an open mind. Respecting the fact that changing from fossil fuel towards all-electric melting requires a significant change in mindset and most likely a substantial amount of research and development.

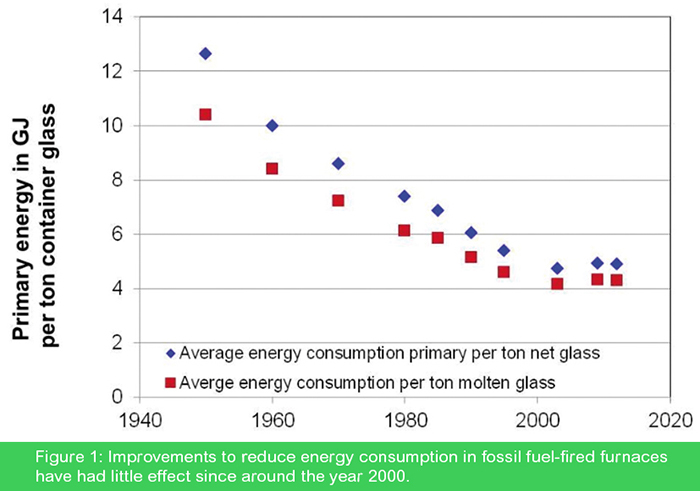

As well as governments, glass industry customers have started to complain about glass manufacturing-related emissions. Over the last 10 years, a huge increase of electrical power usage has been witnessed in glass melting tanks, specifically in special glasses but also in container glass.

Basically, it is possible for the glass industry to switch to all-electric melting, at least from a melting technology perspective. Obviously, some research will be required and there will be specific problems, like how to manage or control redox, high cullet percentages and bigger pull rates. However, the glass industry has managed to solve bigger problems than these in the past, so there is no need to fear what lies ahead. It is time to face the challenges and start working on this important change in melting technology.

The 2018 GlassTrend spring seminar was dedicated to CO2 neutral glass production and 92 participants kicked different solution ideas around to build their own opinions on how to move forward. It seems the biggest show stopper will be that each individual glass manufacturer, however big or small, will not want to be the first to take the risk, in case of running into unforeseeable problems. There also seems to be a disconnect between senior management, finance, marketing and manufacturing.

A technology change of this magnitude will have an impact on the whole business and perhaps the industry needs to start looking at all aspects of their business, even if this makes the problem more complex. For example, CO2-free bottle manufacturing could have a hugely positive impact on marketing, especially now that plastics are under major pressure. Could it represent an opportunity for the industry to get back a big part of the non-alcoholic beverage packaging market, while remaining in the beer and spirits business?

It should be re-emphasised that the interest, activity and desire for collaboration Eurotherm has on this subject comes from the fact that we care about the world in which we live, both for us and our children. Being involved in these discussions, it seems to us that it is becoming vital to move forward. To sit together on a corporate level and figure out the future of the glass industry like Michael Owens, Edward Libbey, Alastair Pilkington and Otto Schott did in the past.

In the near future, the world’s destiny will demand answers from everyone. As Mario Andretti said: “If you wait, all that happens is that you get older” (6). This message is just as applicable today but glassmakers should now question if it will still apply to the next generation. Should this typically traditional industry take that risk for granted?

About the author:

René Meuleman is Eurotherm’s Business Leader for Global Glass